Barren-ground caribou (Photo: Catherine Graydon)

Species at Risk Updates – Upcoming Community Consultations on Barren-ground Caribou, Grizzly Bear and Little Brown Myotis

September 29, 2017

This fall, in late October and early November 2017, the WRRB and the Tłįchǫ Government will be travelling to Tłįchǫ communities to discuss three species that have been assessed as species at risk. In April 2017, the Species at Risk Committee (SARC) assessed the biological status of barren-ground caribou in the NWT excluding the Porcupine Caribou herd as Threatened, and both grizzly bears and little brown myotis (a type of bat) as species of Special Concern. SARC considered Porcupine caribou separately as a geographically distinct population and assessed these caribou as not at risk in the NWT.

Now, the Conference of Management Authorities (CMA) is preparing to make a decision on whether to add these species to the NWT List of Species at Risk. Information gathered from community members during the joint consultations will be used in making listing decisions. The CMA will be required to sign a consensus agreement on the listing of these species by April 2018.

Detailed information on each of these species will be shared at the community sessions, but here are some key points.

Barren-ground Caribou

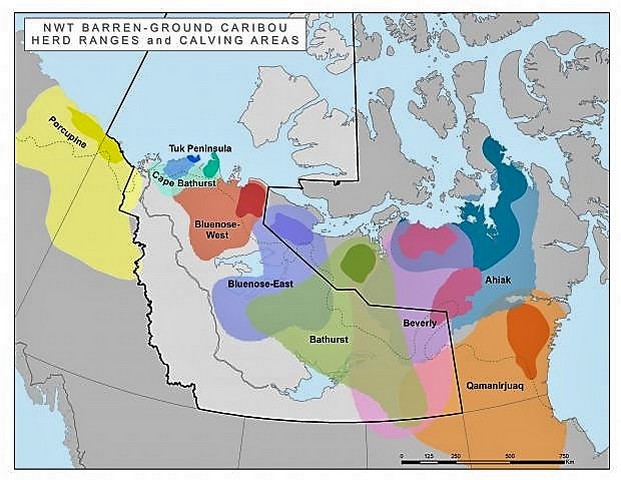

Many of Canada’s barren-ground caribou herds are decreasing. The Bathurst caribou herd, for example, once among the country’s largest at almost half a million animals, is now down to an estimated 20,000. The Bluenose-East caribou herd, also found in Wek’èezhìı, fell from an estimated 68,295 caribou in 2013 to 38,592 in 2015 –a decline of about 43% in population size.

NWT Barren-ground caribou herd range and calving areas. Calving areas are indicated by the darker areas within ranges. Map: GNWT / ENR

Traditional knowledge and scientific observations alike tell us that barren-ground caribou populations rise and fall as part of their natural cycle, but today there are added pressures on caribou, many of them unprecedented and interacting in ways that are not fully understood. Those stressors, ranging from a changing climate to increasing development and human activity on their ranges, are making it more difficult for these caribou to recover.

How are changes to caribou related to what is happening on their landscape –for example, the timing of spring green-up that caribou rely on for birthing and raising their young –or the amount of snow cover? In winter, deep snow or icing may prevent caribou from reaching their food. In summer, insects can interrupt feeding. If vegetation greens too early, caribou may miss the time when plants are most nutritious. Ongoing cumulative changes to the caribou’s environment due to changes in weather and disturbance from increased exploration and development activity likely play a role in declines. Additionally, predation, harvest, and parasites and diseases can all affect caribou numbers.

In its recommendations following the 2016 public hearings on the Bathurst and Bluenose-East caribou herds, the WRRB called for increasing both Tłı̨chǫ knowledge and scientific research into the drivers of the decline in the herds. A number of research and monitoring projects are ongoing in the quest to try to understand why the declines are occurring and how to foster the caribou’s recovery –and more research will be needed in future.

Are barren-ground caribou considered species at risk at a national level (in Canada)?

- Nationally, in December 2016, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assessed all Barren-ground caribou in Canada as Threatened, a designation that means the species is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation (disappearance from an area) or extinction (no longer exists anywhere).

- These caribou are now being considered for listing as a Threatened species in Canada under the federal Species at Risk Act.

Grizzly bear on the barrenlands. Photo: Catherine Graydon

Grizzly Bear

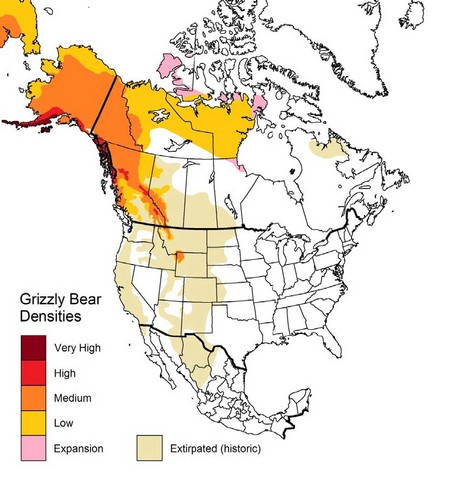

Grizzly bears are extremely sensitive to habitat disturbance and have difficulty recovering from population declines. In the southern parts of their ranges, while grizzly bear distribution has been relatively stable for the last few decades, some populations are small or in decline as human presence encroaches and grizzly bear habitat is fragmented, isolating local populations and putting them at risk. Their historical range in Canada has been reduced dramatically to the point where grizzly bears have been completely extirpated (no longer exist) from their former ranges in the interior of southern British Columbia, the prairies and the Ungava region of Labrador and northern Quebec. Today, grizzly bears are mostly found in Northwestern Canada.

Map showing historic and current range of grizzly bears in North America. Population densities, a measure of the number of grizzly bears per unit of area, are also shown. Note that in most of the NWT, grizzly bears are considered low density, meaning their numbers are relatively small and spread out over a large area. Source: COSEWIC Status and Assessment Report - Grizzly Bear (2013)

The northern part of their range is relatively undisturbed, but this is changing with increasing pressures from development and human activity. Grizzly bears require large home ranges and proper denning sites, and they tend to avoid human activity where possible. This avoidance may cause the bears to abandon important sections of their home range if it is undergoing exploration or development. Increased impacts to their habitat from industrial activity and roads could pose a significant threat. Roads into previously inaccessible areas may also pose a risk of mortality for grizzly bears as the potential for increasing instances of human-grizzly bear interactions becomes greater.

There are a number of biological characteristics that make grizzly bears vulnerable to these threats and others. In the NWT, grizzly bears are found at naturally low densities (only a few animals spread out in a large area), and their population is considered small. Grizzly bears reach sexual maturity late –females begin mating usually between 5 and 7 years of age, and their “reproductive output” is very low: litter sizes are one to three cubs. The number of cubs and their likelihood of surviving depends on the availability of food. As well, grizzly bears must den for several months over the winter, which also makes them vulnerable to disturbances.

Because of this combination of biological characteristics and identified threats, NWT SARC assessed grizzly bears as Special Concern in the NWT. A species of Special Concern is sensitive to environmental factors and may become threatened or endangered if negative factors aren't addressed.

Are grizzly bears considered species at risk at a national level (in Canada)?

- COSEWIC assessed the population of grizzly bears that occur in the NWT (Western population) as Special Concern in Canada in 2012.

- The grizzly bear—Western population is being recommended for listing as a species of Special Concern under the federal Species at Risk Act.

Little brown bat. Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service By U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters [Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0]

Little Brown Myotis

The health and numbers of several bat species in North America are at risk from a relatively new disease—white-nose syndrome, a disease caused by a fungus that grows over the bats’ faces while they hibernate in winter, a time when they are most vulnerable. The fungus grows in humid cold environments typical of the caves where bats hibernate. The disease disturbs their hibernation. When bats are disturbed during their winter hibernation, they use up vital energy reserves needed to survive the winter. Bats with white-nose syndrome show loss of body fat and unusual behaviour during winter, such as flying outside in the day when temperatures are at or below freezing, using up energy reserves. Very often they die of the disease.

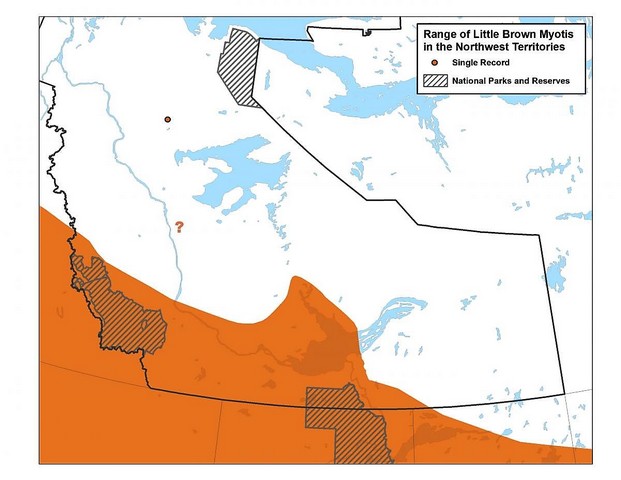

The little brown myotis is one of the species of bats that is affected by this disease. In eastern Canada, little brown myotis populations impacted by white-nose syndrome have declined by 94%. The little brown bat has been “functionally extirpated” by white-nose syndrome in some areas of eastern Canada. This means that their numbers are so low they no longer play a significant role in ecosystem function. Although it is not currently present in the NWT, white-nose syndrome is spreading, and it could reach NWT populations in one or two decades or sooner.

Range of little brown myotis in the NWT. The northern limit of its range is not well known, but a little brown myotis was found in Colville Lake in 2012. Source: GNWT / NWT Species at Risk

Other threats to the little brown myotis in the NWT include loss or disturbance of their habitat including human impacts at hibernacula (winter rooting sites) and removal of maternity roosts.

Because of sudden and dramatic declines due to white-nose syndrome in eastern Canada and the United States, the little brown myotis was emergency listed under the federal Species at Risk Act in 2014. A national strategy is being developed.

Here in the NWT, the little brown myotis was assessed as a species of Special Concern because of its high vulnerability to white-nose syndrome. If it comes north, the disease could have catastrophic consequences for the little brown myotis, as well as for another bat species, the Northern myotis, found to the south of Wek’èezhìı, if no action is taken.

Should barren-ground caribou, grizzly bears and little brown myotis be added to the NWT list of Species at Risk?

- The public is invited to comment on the potential addition of barren-ground caribou, grizzly bear, and little brown myotis to the Northwest Territories (NWT) List of Species at Risk. You can attend the information sessions in your community this fall and give your input. Check the WRRB Facebook page for the dates of upcoming meetings in each Tłįchǫ community.

- Visit the NWT Species at Risk website for Fact Sheets and assessments reports for each of these species.

Fact Box: Conference of Management Authorities (CMA)

- Consists of the wildlife co-management boards and governments that share management responsibility for the conservation and recovery of species at risk in the NWT.

- Makes decisions on listing, conservation, management, and recovery of species that may be at risk of disappearing from the NWT.

Fact Box: Species at risk listing process

- Once a species has been added to the NWT list of Species at Risk, recovery planning begins. In the case of a Threatened species, a recovery strategy is developed to identify what needs to be done to “recover” a species and protect it from further decline. In the case of a species of Special Concern, a management plan is developed.

- Check here to keep track of species going through the NWT Species at Risk process.